Brassaï, originally as Gyula Halász, Hungarian-born French photographer, painter, writer, film artist. The artist was born in Brasov on September 9, 1899 from Armenian mother and Hungarian father. Brassai studied fine art in Budapest and in Berlin with interruptions between 1918 and 1922. After graduating, he went to Paris to try his luck at the age of twenty-five.

In Paris he made money from sending articles in Hungarian to the annexed Slovak, Romanian, and Yugoslavian territories. He was a journalist, cartoonist and even sent sports coverage of the 1924 Paris Olympics as well. He reported Hungarian, French and German newspapers, illustrated his articles with his drawings, took photos from 1929 as well.

Came into contact with photography when initially he bought photographs taken by others for his articles. At this time he had no camera. Soon, he understood that it is more economical if he illustrated his articles with his own photos.

He obtained his own camera at the beginning of 1930, a Voigtländer-Berg Heil, 6×9 cm, D: 4.5, then a Rolleiflex in 1935. He set up a lab in another room in the Hotel Glacière, where he lived than.

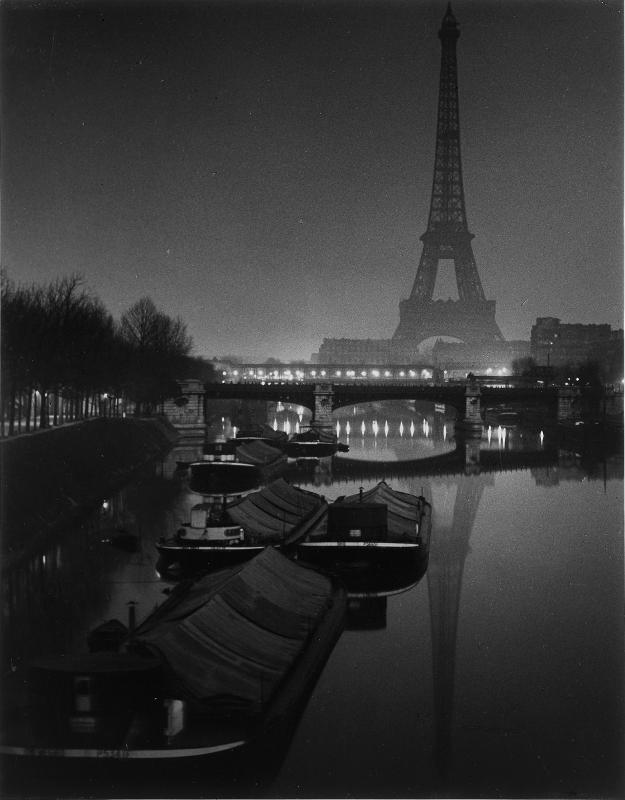

The knowledge, including shooting night shots came from André Kertész. This subsequently led to conflicts between the two. Kertész in his memoirs accused him of stealing ideias and ingratitude. At this time his album Paris de nuit (Paris night) was released (Paris: Arts et Métiers Graphiques, preface. Paul Morand) in late 1932 under the name Brassaï. The photographer, photographing just two years, soon became world famous thanks to the album.

This quick recognition by international standards is a rare phenomenon, which is based on that Brassaï had a high level of visual culture without art degree. This is evident that the teachings of Kertesz also proved effective. Definitely he was influenced by the photos of Paris (Paris: Jouquires, 1930) of Eugene Atget (1856-1927).

The photos of Paris de nuit was also a pioneer technically, because before that night photography – especially in contiguous system – was almost no precedent. Beyond the technical signicance of the photos the lyricism, which is strengthen by transitional tones and the capturing of social weakness witnessing dramatic nature by avoiding demagogy astounded the contemporaries, and it still demonstrates significant values.

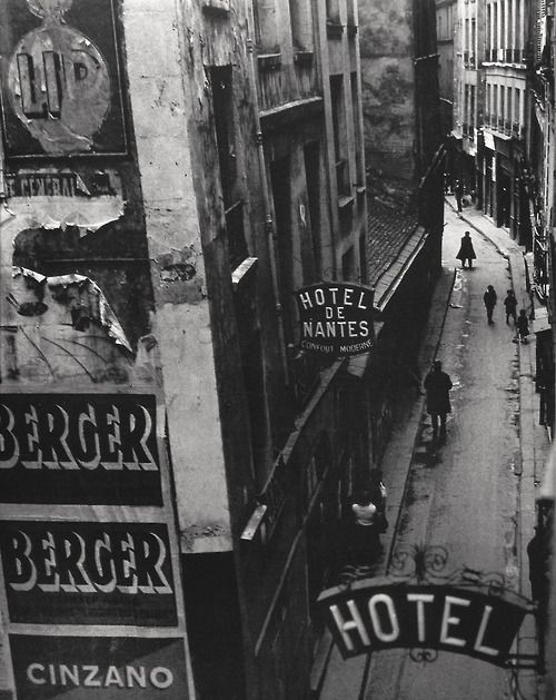

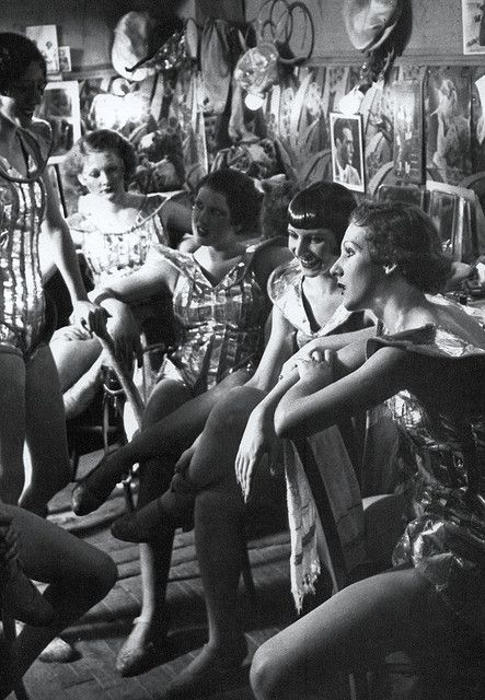

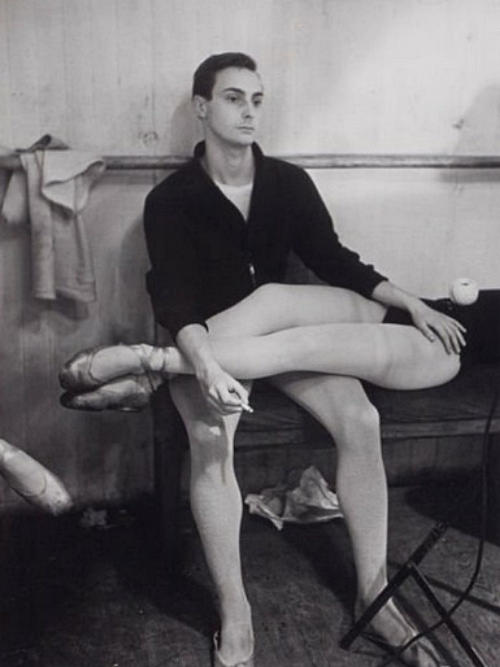

The layout of all the album pages are quite clearly brought from the compositional knowledge of fine art practice, discipline holding in frame. Many images was left out from the album Brassaï liked. These, as well as later photographs capturing the Paris nightlife in those days did not make publishing eventhough the French capital was not prude back then. Pictures captured in Public Houses, people enjoying drugs, prostitutes, pederasts among his works. These photos was finally published in 1976 in Le Paris secret des Années 30 – The Secret Paris of the thirties (Paris: Gallimard, London: Thames and Hudson, New York: Pantheon Books). Only the modest photographs on this topic could appear at The night in Paris.

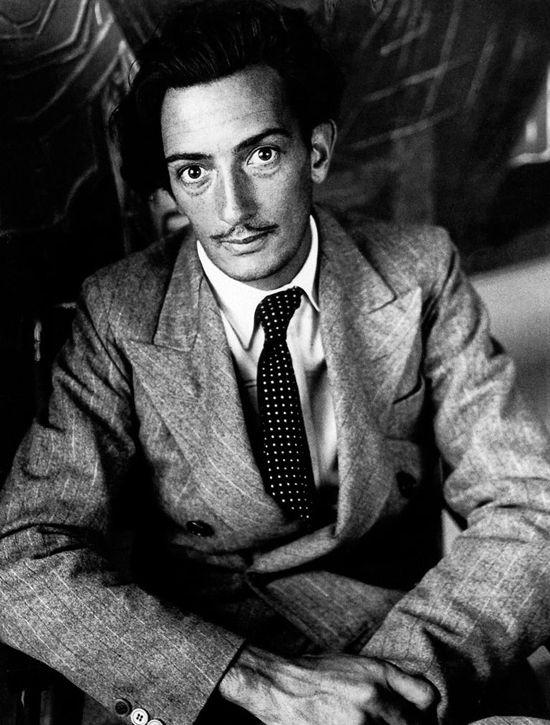

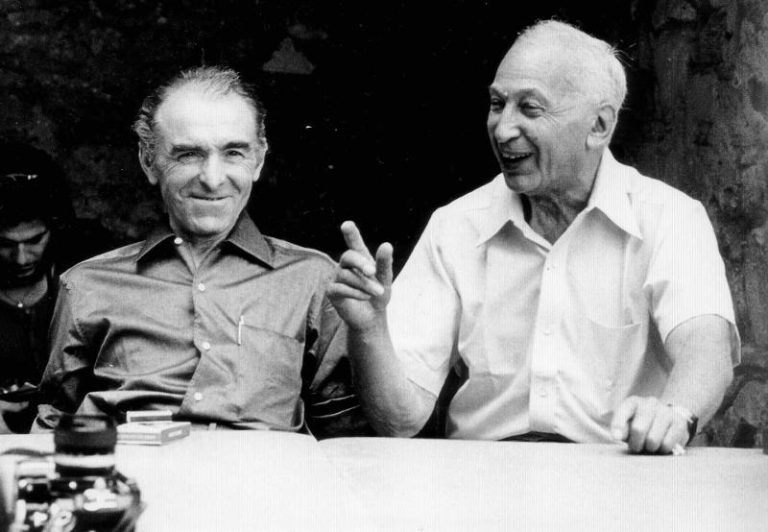

Brassai was in a good personal and professional relationship with Picasso. It’s evidence is his two books (Les Sculptures de Picasso – Picasso’s sculptures – Paris La Chêne 1949; Conversation avec Picasso – Conversation with Picasso – Paris, Gallimard, 1964 – the latter in Hungarian in 1968, Budapest). Between 1930-1963 he worked as a photographer for various magazines, such as Minotaure, Verve, Picture Post, Lilliput, Coronet, Labyrinthe, Réalités, Plaisirs de France. From 1937 he worked for Harper’s Bazaar US women’s fashion magazine, where he was granted full freedom of choice of the subject, his photographs appeared in the Magazine for a quarter of a century.

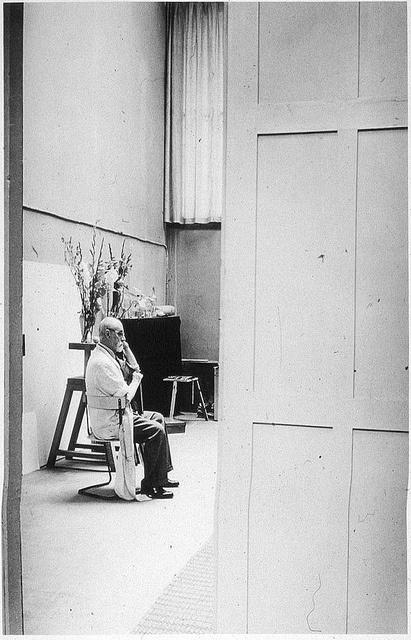

After the war he again began to photograph his favorite city, the details of the sidewalks, crumbling building corners, filling human content in graffiti as well. He was interested in space and forms, but still captured static subjects and settings. In the fifties he planned theatrical sets and carpets. The film he shot in the Paris zoo won prize at the Cannes Film Festival in 1956. He published the book Artists in my Life in 1982 about artists, art dealers and friends with their photos as well.

In 1976 he was honored the Legion of Honor and in 1978 the Grand National Photography award. “The Eye of Paris” – as his friend, Henry Miller, American writer called him – was died on 8th of July, 1984 on the Riviera, and he rests in the Montparnasse cemetery.